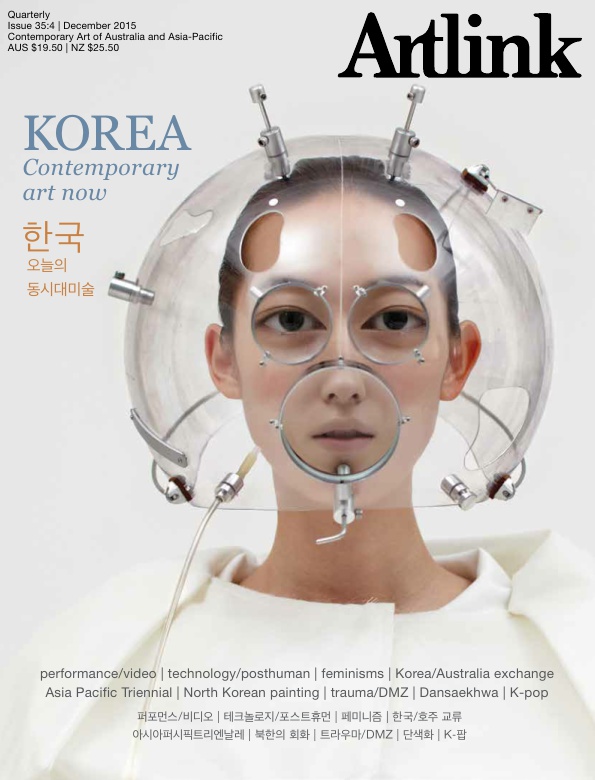

From the outside view, how would it be seen the Korean culture and art scene? Australia is one of the most active countries that have contemplated on the relation with Asia. David Pledger, who has been an active writer in both Korea and Australia, researches the cultural identity of Korea in the aspect of national economy and policy. Pledger analyzed the identity and force of Korean culture with covering various subjects including the division of North and South Korea and the issue of national identity, IMF crisis in Asia, art support policy and trend of Korean Wave, called "Hanryu." This text was originally published at the quarterly magazine, Platform Paper, by Cun'ency House, Australia, and is rewritten by the author for the Artlink's special bilingual issue KOREA contempo- ratyan now, Vol.35:4, Dec. 2015, for which KAMS provided advisoty and translation services.

The idea that Asia is not one country is just starting to take hold in Australia. For decades our foreign policy has lived in the shadows of White Australia, a policy that created a mindset preventing any deep appreciation of the rich cultural, ethnic and racial tapestry that confounds definition of the Asian continent. This policy deficit was somewhat tempered by the 2012 Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, a whole-of-government acknowledgment of Asia and its significance to Australia’s history and identity. In the last few years, bilateral trade and cooperation agreements with Indonesia, India, Japan and China have brought us back to a future imagined by former Australian prime ministers Gough Whitlam and Paul Keating in which Australia’s and Asia’s future are inextricably linked.

Unfortunately, any allusions to the role of culture in these new arrangements are desultory. It is a particularly Australian blind spot that imperils a furthering of the thinking and engagement with Asia and which places it in contrast to other developed countries and states in the East and Southeast Asian regions. For example, the value of cultural agency in international engagement is high in Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan and a big impression is now being made by Indonesia. But it is the success of the cultural program of the Republic of Korea (Korea) over the last twenty years that provides compelling instruction.

above) Park Chan-kyong, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits, 2013, HD film. A documentary/fantasy construct of the history of oppression of the religious rites of Korean shamanism, an exclusive province of women, in which forgiveness and reconciliation is central. Park uses the life of the great shaman Kim Keum-wha who has been honoured as an intangible living treasure.

above) Park Chan-kyong, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits, 2013, HD film. A documentary/fantasy construct of the history of oppression of the religious rites of Korean shamanism, an exclusive province of women, in which forgiveness and reconciliation is central. Park uses the life of the great shaman Kim Keum-wha who has been honoured as an intangible living treasure.

Korea punches at around the same weight as Australia in terms of its potential to wield soft power through cultural activity. Its trajectory often intersects and competes with ours which makes Korea a featured protagonist in Australia’s 21st-century Asian narrative. There are of course fundamental and idiosyncratic differences between Korea and Australia in history, geography, evolution of political culture and cultural politics but a brief analysis of the how and why of Korea’s achievements can reveal useful information, especially in the story of a country that understands the value of its national identity, and the centrality of the arts in defining and communicating it.

I first worked in South Korea in 1993, one year after a civilian was elected President for the first time in 40 years. Back then, countries were classified as first, second or third world. Against most indicators South Korea was a second world country struggling in the aftermath of a decades-long cycle of war, invasion, occupation and dictatorship. Pop star PSY’s suburb, Gangnam, was a dream (or an hallucination) way beyond household income thresholds that barely registered on the OECD gazette. Today, Korea is a regional powerhouse. How did it transform itself in one generation?

From the late 1990s, the “Korean Wave” or Hanryu washed up on the shores of neighbouring countries. Artist and artisan-led, Korean TV soap-operas, magazines, films, fashion, pop music and latterly the performing arts made a phenomenal impact, exceeding the expectations of a population of 50 million umbilically cut from its northern half and vulnerable to the volatile geopolitics of the region. Even China was smitten. On the back of this wave, Korea turned itself inside-out from a country beset by a crippling identity crisis to a nation hell-bent on internationalising itself from the ground up. Two main factors accelerated the momentum: the success of Korea’s co-hosting with Japan of the 2002 World Cup and a shift in the nation’s political dynamic towards an active appreciation of the value of culture in the internationalisation process.

Dutchman Guus Hiddink is a national hero in Korea. As coach of the national soccer team, Hiddink took the country into the 2002 World Cup semi-finals, one better than its co-host, Japan. Whilst the argument that a nation’s sporting success is directly linked to a positive national identity is anathema to much of the Australian arts community, it doesn’t play that way in Korea. On the day of the semi-final, fellow artists and cultural operators expressed wonderment at the feeling on the streets in Seoul where ten million Koreans stepped out to celebrate going past their old rival in anticipation of greater glory. Old and young, usually separated by tradition and custom, joined hands as one, the latter dressed in costumes made from cut-ups of the Korean flag, an action previously deemed a treasonable offence. The obstacles of inter-generationalism were submerged that night and never resurfaced with the same potency. More importantly, Korea’s chip on its shoulder with Japan – fuelled by the latter’s brutal occupation of the peninsula in the early-to-mid 20th century – evaporated in the blink of a penalty shot.

above) Park Chan-kyong, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits, 2013, HD film. Courtesy the artist

above) Park Chan-kyong, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits, 2013, HD film. Courtesy the artist

The second factor played out very publicly in the global economy. Sent bankrupt by the 1997 Asian economic meltdown – or, if you are Asian, the IMF crisis – Korea’s Federal Government artfully restructured the nation’s financial frameworks so that within a decade it had resumed its role as the world’s fastest-growing economy. One of its strategies was to place the arts at the vanguard of its policy because Korea’s political culture understood that for its economic motivations to be understood, the basic Korean character and sensibility needed to be explained, communicated and appreciated.

And so it strategically funded the cultural sector: regionally, by instigating an atmosphere of productive competition; nationally, by promoting Korean culture to a growing domestic audience; and internationally, by committing funds to a new policy of international collaborations and touring. Significant initiatives underpinning this strategy are the screen quotas on Korean films which enabled the domestic viability and international success of the Korean film industry; the establishment of the Korean National University of Arts (KNUA), which brought new levels of excellence and expertise into the professional arts community and the Asian Culture Hub City in Gwangju, an ambitious concept in urban design linking artistic thinking and practice to local and regional questions of Asian identity. The key driver of this development is indeed identity, or more precisely, the need to understand and communicate the value of one’s own identifying parts so as to distinguish oneself from others. As the Australian artist Juan Davila advised Australia more than 30 years ago: “We should find a dialogue constituting ourselves as a difference, not as a peripheral ‘another’, but as a sustained contradiction.”1)

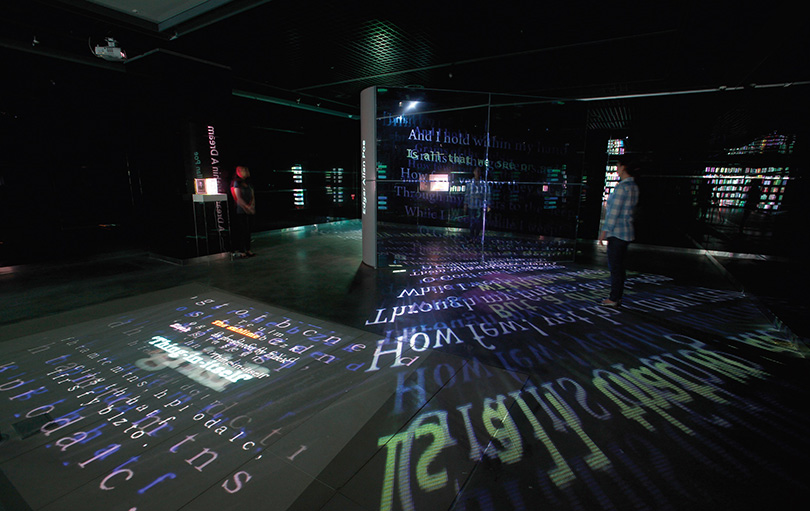

above) Airan Kang A Dream within a Dream, 2013, 3-channel video, steel, mirror. Courtesy the artist

above) Airan Kang A Dream within a Dream, 2013, 3-channel video, steel, mirror. Courtesy the artist

Through the Asialink Arts Residency Program, an alumni of Korea-informed artists and curators continues to expand. Yvonne Boag, a 1995 Asialink resident, has sustained perhaps the longest connection with Korea for over twenty years; going beyond her own art practice, she curated, collaborated and acted as consultant for many and varied exchange projects. In partnership with Asialink Arts, Kim Hong Hee, founder of privately-run Ssamzie Space, empowered a generation of Australian artists and curators to explore Seoul and surrounds in the 2000s. She also hosted curators who have maintained ties with Korea like Sarah Tutton and Alexie Glass-Kantor and artists such as Ian Haig, Larissa Hjorth, Richard Giblett and Ash Keating. With the rise and rise of government-supported residency spaces in Seoul, Artspace in Sydney has maintained a commitment to hosting reciprocal residencies in partnership with Goyang Art Studio (affiliated with the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art) now in its fifth year and the National Art Studio, Changdong, supporting artists like Yongseok Oh, Locust Jones, Guy Benfield with Hae-Young Seo and Kevin Platt in the exchange

of ideas.* 1)

1)Juan Davila, artist’s statement in ARC/Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, D’un autre continent: L’Australie le reve et le reel, exhibition catalogue, Paris 1983, p. 102 (also quoted in Chris McAuliffe, ‘Living the Dream’, Meanjin #3, 2012, p. 63.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney (MCA) has also recently announced its second major exchange project in four years, with New Romance: Art and the Posthuman, co-curated by Anna Davis Curator at the MCA and Houngcheol Choi, Curator at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea for exhibition in Seoul and Sydney. This follows the earlier collaboration between the same institutions with Tell Me Tell Me: Australian and Korean Art 1976–2011 presented in 2011 and 2012 at both sites.

above) Brook Andrew Loop. A Model of how the world operates, 2008, wall painting, animated neon, electrical components, installed at MMCA, Tell me Tell me: Australian and Korean Art 1976–2011. Courtesy MMCA, MCA and the artist

above) Brook Andrew Loop. A Model of how the world operates, 2008, wall painting, animated neon, electrical components, installed at MMCA, Tell me Tell me: Australian and Korean Art 1976–2011. Courtesy MMCA, MCA and the artist

In 20th-century Korea this contradiction was propagated by a narrative of resistance to successive occupations by Japan and America. In very different ways, both occupations threatened Korean language and culture but instilled a sense of purpose at all levels of society. Local political and cultural influence eventually prevailed and this resilience is manifest in Korea’s current global agency.

The ever-present elephant in the room – the separation from the North – bears down heavily on this analysis. It is impossible to know what role it plays in this equation other than to say that if occupation inspires resistance then separation conjures grief, and to conquer grief, a new life must be made, a new identity forged. Which is what Korea did – by giving culture the central role in shaping a contemporary identity, and also by appreciating the value of the artist as mediator, communicator and interpreter – a secular shaman in the modern incarnation of this uniquely conflicted country.

A final distinction of the Korean cultural sector is its innate bureaucratic nature. A lasting impression (and lesson) was given me during my first appointment at KNUA. When attempting to secure some extra rehearsal space for a production, the departmental office manager regarded my efforts with a defiant smile and said: “This is not India. We are far more bureaucratic than India.” Whilst flexibility has become much more commonplace for the foreign artist working in Korea, the vestiges of this attitude and its cultural source remain vivid in the larger cultural institutions.

These final comments are not so much a critique but reflections on Korea’s points of difference that arise out of that identity that it has so artfully carved over the last twenty years. But, even with these traits, there is no doubt that Korea Mk 2015 is the very model of a modern major middle power exercising it softly and on its own terms.

※ This is an expanded version of the Korean chapter of Platform Papers #36, August 2013, “Re-Valuing the Artist in the New World Order”̋ by David Pledger, published by Currency House, Melbourne; reprinted by kind permission.

David Pledger / Artist

A cultural operator who has created international collaborations in Europe and Asia across the performing, visual and media arts. As founding artistic director of not yet it’s difficult, one of Australia’s leading interdisciplinary arts companies, he was part of the first wave of Australian artists to engage in the East Asian region and the first non-Korean to be invited to join the staff of the Korean National University of Arts.