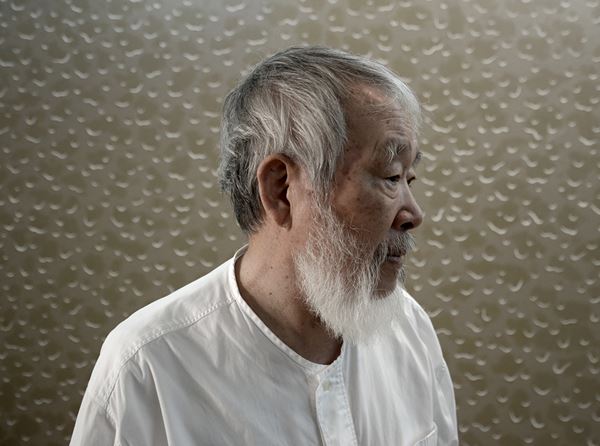

Kim Tschang-Yeul. ⓒthe artist.

Kim Tschang-Yeul turns 90 this December, following an illustrious career that played a crucial role in bringing post-war Korean painting into the modern and contemporary art canon. Long celebrated for pensive depictions of water drops, the esteemed artist uses dual languages of abstraction and hyperrealism to articulate the psychological traumas inflicted by a tumultuous past. Last month, New York's Tina Kim Gallery unveiled its first solo exhibition of the artist's earlier works, titled 《New York to Paris》 (24 October–7 December 2019). The paintings on view provide a remarkable glimpse into a formative period marked by a transition from nonfigurative forms, and the debut of his signature water drops.

Understanding Kim's background is essential to grasping the meaning behind his contemplative paintings. Born in Maengsan, a town that is now in North Korea, the artist came of age in a historical time marred sequentially by Japanese occupation, communism, and civil war—the latter of which he witnessed from close range as a soldier. Following the war, Kim helped found the mid-1950s and early 1960s Korean Informel movement, which embraced abstraction as a turn away from traditional artistic norms. In 1965, a scholarship from the Rockefeller Foundation enabled him to move to New York, where he became acquainted with the trends that pervaded mid-century American art. Kim, however, found New York inhospitable, and relocated to Paris in 1969.

Exhibition view of Kim Tschang-Yeul, 《New York to Paris》, Tina Kim Gallery, New York (24 October–7 December 2019). ⓒthe artist and Tina Kim Gallery.

The exhibition opens with a group of works created soon after this juncture in Kim's life. It comprises paintings wherein oozing forms protrude from various geometric configurations, and undulating lines wrap around nuclei of gradient circles. These compositions allude to the visual vocabularies of Minimalism and Op Art—most tellingly in the way that sparse backgrounds give way to swelling, ambiguous shapes; Kim fittingly referred to the canvases as 'paintings of the intestines', in light of their apparent biomorphism. The rippling of black and white lines also calls to mind Op Art's play on ocular perception, acting as a precursor to the illusionist depictions of water drops that would define Kim's practice for over four decades to come.

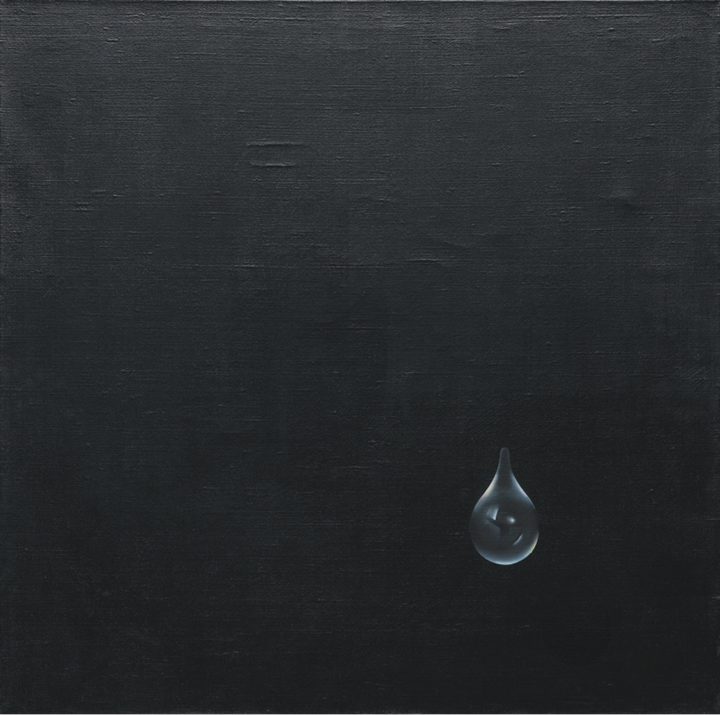

An empty stretch of the gallery demarcates these earlier works from a pair of Kim's inaugural water drop paintings, first shown at Paris' Salon de Mai in 1970. Each featuring a magnified water drop on a stark canvas, the paintings' trompe l' oeil appearances belie a minimalist approach, in which gentle dabs of whites, blues, and greys are used to simulate translucence. The pair is followed by a succession of paintings created through to the early 1980s—some sparse, with others bearing tight clusters of droplets. In 〈Il pleut〉 (1973), tiny water drops slash across the surface of a wood veneer sheet. It directly references a concrete poem published by the avant-garde writer Guillaume Apollinaire in 1916, following his service in World War I. By replicating the poem, Kim paid homage to a Surrealist trailblazer who similarly lived through times of violent upheaval.

Kim Tschang-Yeul, 〈Événement de la nuit〉, 1970. Oil on canvas. 70x70cm. ⓒthe artist and Tina Kim Gallery.

Although he has resided in Europe for the majority of his life, the artist infused his works with the Taoist principles of his upbringing, characterising water as an amorphous entity imbued with the power to dissolve and to purify. In working through the memories of a painful past, he found beauty in austerity, and solace in meditative repetition. Kim's pioneering approach to artmaking pushed abstract painting beyond its confines, and paved the way for new generations of artists working in an increasingly cosmopolitan world. In 2016, the Korean government erected a museum in his honour on the southern island of Jeju, to which he donated over 200 works from his archive. It stands as a testament to the important contributions that he made to 20th-century art, both in Korea and around the globe.

In this conversation, Kim discusses his beginnings in New York and Paris, early influences, and the formulation of his famed water drop paintings.

Exhibition view of Kim Tschang-Yeul, 《New York to Paris》, Tina Kim Gallery, New York (24 October–7 December 2019). ⓒthe artist and Tina Kim Gallery.

※ Click to Read the Full Article on OCULA: Kim Tschang-Yeul: Art Without Ego (https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/kim-tschang-yeul/)

※ This article was originally published in OCULA(https://ocula.com) on 22 NOV 2019 and reposted under authority of a partnership between KAMS and OCULA.

Vivian Chui

Ocula